As beautiful and adaptable as the evergreen, The Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe has been a hallmark of the Kitsap Peninsula for over 10,000 years.

Ancient Landscape

The S’Klallams thrived through a seasonal connection to the changing climates. In the warm summer months, they roamed semi-nomadically and re-visited fishing holes and hunting/gathering sites. During the cold winter rains, they congregated in plank and pole longhouses to practice religious ceremonies and spend time with loved ones.

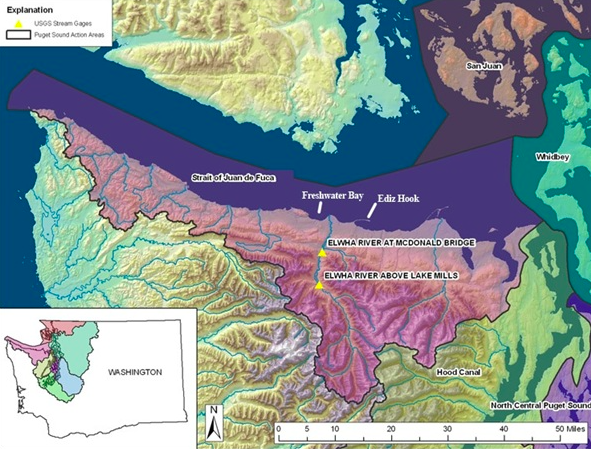

The purple region indicates the S’Klallam area. Source: Klallam Library

The S’Klallam footprint, though environmentally small, was a massive territory. S’Klallams were historically around 15 tribes that enjoyed friendly relations between themselves and neighboring Salish Tribes, like the Twana Tribe. They even shared natural resources, like the coveted Hood Canal fishing sites.

Culture, Traditions, and Conflict

The Port Gamble S’Klallams enjoyed a rich life. They ate delicious foods like smoked salmon and baked clams, created an evolving yet distinct artistic style, and a language that was once “forced to be forgotten.” These traditions continued for generations – until the first contact with Europeans.

Illness ravaged the Tribe. The Hudson Bay Company initially reported some 1,500 S’Klallams in 1845. But after diseases such as smallpox had run their course, estimates dwindled to only 400. Yet, sturdy as the evergreen, S’Klallams survived.

However, the problems from European contact were far from over. Next, disputes between Settlers and S’Klallams began drawing blood and sparking violence over resources and land. In November of 1853, the S’Klallams lost 438,430 acres of ancestral lands in The Treaty of Point No Point. It contained confusing language, inconsistencies in the agreements, and western private property concepts not understood by the communal S’Klallam. They also forced the Tribe to relocate to the Skokomish Reservation, 100 to 180 miles away from home along the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Hood Canal.

Recognition and Resilience

Over 80 years later, the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe successfully petitioned the federal government to officially recognize their independent tribal status. In 1936, “the United States government purchased the 1,231-acre Port Gamble S’Klallam Reservation.”

Despite this, settler dissent led to acts of violence: “In 1939, gasoline was poured on some of the houses at Point Julia and the village was burned to the ground. Some of the older people didn’t want to leave the spit, having lived there most of their lives. One tribal member recalls an elder who had to be forced out of her home. She sat in an old chair while they were packing her stuff out. She was sitting there crying and talking to herself and singing in Indian. It was pitiful to watch. Under pressure from the federal government, the S’Klallams relocated on the bluff above Point Julia.”

As the Tribe states, “From the time of white settlement, until their treaty rights were recognized by a court decision in the 1970s, the S’Klallam Nation faced fundamental challenges to its existence.”

S’Klallams Today

Continued fishing disputes couldn’t shake the S’Klallams, who began to develop economically into the success the Tribe now enjoys. Today, Port Gamble S’Klallam commerce thrives: Tribe owned businesses like the Point Casino, Heronswood Botanical Garden, Gliding Eagle Market demonstrate their adaptability and perseverance.

S’Klallams harvest resources in many of the same ways as their ancestors. The Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribal Headquarters sits on the Sound, just south of Point Julia. Here, S’Klallams find community, regulate Tribal business, govern, and provide social services. The Headquarters houses a vast digital library of information and traditions to preserve the community and culture for generations to come, passing on the resilience of a people akin to the evergreen trees that surround.

Facebook

Facebook

X

X

Pinterest

Pinterest

Copy Link

Copy Link